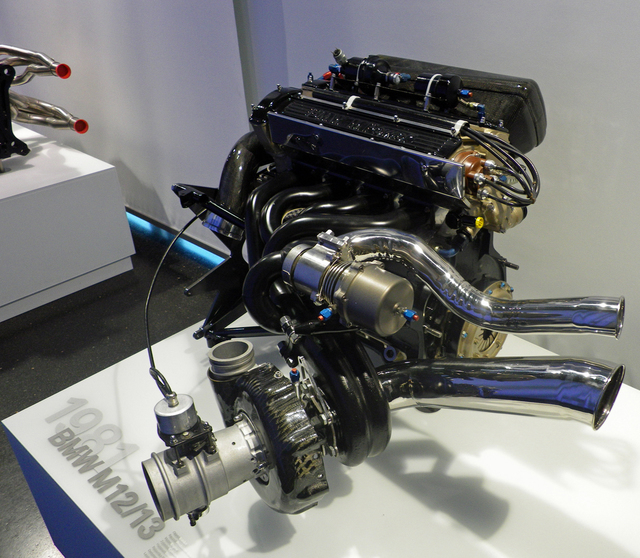

Many might remember the amazing shriek of the BMW V10 powering the Williams F1 cars from 2000-2005. The motor was regarded as the most powerful for the time, as it spat out close to 1,000 horsepower. However as impressive as those figures are, the auto titan produced a powerplant two decades earlier with even more power and half the size. Firey, unreliable, and incredibly impressive, BMW’s M12/M13 engine helped define the most excessive era in Formula One, and it did it all with a block from a humble road car.

The M10 from a BMW 1500 Neue Klasse was what laid the foundation for the M12/M13. Only four cylinders producing a meager 80 horsepower, this anemic powerplant started life in the sixties to get a small sedan from point A to B, and certainly, the engineers at BMW probably had no idea that they would, in the span of two decades, stretch the potential of this motor as far as they did.

From the sixties onwards, the governing bodies demanded that the engines in Formula One machines maintain displacements of either 3.0 liters naturally aspirated, or 1.5 liters with forced induction. While BMW had no intent of turning their modest M10 into a fire-spitting monster, a small intermediary development opened the doors for big-budget racing in the world’s most prestigious racing category.

That second step came in the form of a small, unassuming sedan. While in the States, the Chevrolet Corvair had little success as one of the first production cars fitted with a turbocharger, but several years later, it was the nimble, boxy BMW 2002 Turbo that enjoyed success as the first turbocharged production car in Europe. Once this car made its way onto the market, people began to understand the potential the turbocharger had in production cars and sports cars.

Still, it was a stretch to consider that this engine would eventually win a Formula One World Championship. Again, one step was required before this production car-based motor would ever reach the upper strata of motorsport. BMW engine guru Paul Rosche began using a 1,400 cc version of this motor to compete in DTM, and though its drivability and reliability weren’t enviable, the 350 horsepower it produced off the bat illustrated the potential this powerplant had.

With this indication, the bright minds at BMW began developing the M12 for Brabham’s Formula One car. In it’s first season, the BMW engine ran in one car while their dependable, but soon-to-be-obsolete Cosworth DFV — a N/A V8 – was used in another. Teething problems kept the car from seeing much success in 1982, though the potential was there — Nelson Piquet won the Canadian Grand Prix that year. However, the following year, while comparatively unreliable, the BMW engine was stout and fast enough to secure three wins and the championship.

The power delivery of the M12/M13 was so abrupt that the Brabham designers shifted an outrageous amount of weight to the rear, in hope of aiding in traction.

Many of the multinationals with tailor-made race engines could hardly believe that a road car engine fitted with a turbocharger could work well enough to win. After 1983, the Turbo Era was well underway and in various guises, the BMW M12 and M13 made its way into a variety of other F1 cars, including the contemporary Benettons and Arrows. Though the BMW engine never won another championship, it remained a competitive motor, especially on faster tracks were the turbo lag and monstrous power delivery were less of an issue.

The M12/M13 helped define the turbo era of the 1980s. Excessive, outrageous and spectacular, these fire-breathing monsters were capable of spinning the tires in just about any gear, set new outright speed records at every track they attended, costs millions to develop, and lasted a very short time. In fact, the qualifying specials made for the attainment of pole position were run with their wastegates blanked off, resulting in 80 pounds of boost pressure and somewhere around 1,300 horsepower. These engines, nicknamed “grenades”, would last all of four laps before melting on their way back to the pits. Excessive? Certainly, but it shouldn’t have been any other way.