If you’re a true gearhead, you’re probably curious about all kinds of different engine types and combinations. EngineLabs’ recent Facebook post asked readers to post photos and a quick rundown of their engines, and it generated a fair amount of interest. Here are a handful of those posted we thought you might like. These are real engine projects, built-in garages, by readers just like you.

Cliff Elliott’s “Code Blu” Voodoo-based 2016 Mustang GT is a versatile performer

Cliff Elliott, of Aransas Pass, Texas (near Corpus Christi) calls his 2016 Ford Mustang GT Performance Pack “Code Blu,” and although it’s putting out 615 horsepower and 505 lb-ft of torque at the crank, with an 8,400-rpm redline, it’s very streetable, he says. That’s because it’s built with an emphasis on producing a broad torque curve for Optima Ultimate Street Car Association events.

“My motor makes the most down-low torque of any high-horsepower engine I have seen posted, with 400 lb-ft of torque at the wheels at 3,100 rpm. That’s about 85 more than a GT350 motor,” he says. “I also have a 2016 GT350R, so I have runs of both cars on the same dyno. My motor makes 400-plus lb-ft up to 7,000 rpm. The car has to do everything, from autocross to the road course, to Speed-Stop, and street drive.

“My 85-year-old mother can still hop in the car and drive it. It’s very streetable, and I’ve driven it to South Carolina to Mustang Week from south Texas twice now. I even won the BFGoodrich Autocross both days and the car show in my class in 2018. In 2019, the hurricane canceled all the track events.”

My motor makes the most down-low torque of any high-hp engine I have seen posted, with 400 lb-ft of torque at the wheels at 3,100 rpm. — Cliff Elliott

The 5.2 Voodoo — but with a cross-plane crank — in Cliff Elliott’s 2016 Ford Mustang GT puts out a broad torque curve, ideal for a variety of competition events and reliable street-driving.

For his build, Elliott chose a 2016 Ford 5.2L Voodoo engine, built with a cross-plane crankshaft in place of the Voodoo’s unique flat-plane crank. “It was most likely the first 5.2 OEM-internal Voodoo motor built with a conventional crankshaft, which is what is now available as the Ford Performance 5.2-liter Aluminator XS crate motor,” says Elliott.

Elliott built the engine right before the 2016 SEMA Show to compete in Optima’s Ultimate Street Car Association event, held at the show. With the short-block already done, three weeks before the show, he received what he says was the first set of 5.2 Voodoo heads from Ford Performance available to the public.

“I did a little light polishing on the exhaust ports and polished the chambers on my current engine, but that’s all. The internals are all stock OEM Voodoo internals, just with the conventional crankshaft and cams with the same specs as the Voodoo motors, but with the Coyote firing order.”

The camshafts feature 14 mm of lift and 270 degrees of duration, Elliott says. The new cams add about 15 degrees of duration, the maximum at which he’s still able to use the variable cam timing phasers.

Elliott did some mild massaging on the Voodoo heads, porting and polishing the exhaust ports. He cc'ed the combustion chambers to make sure they were of the same volume. The street-legal 2016 Mustang GT is driven long distances and competes in multiple types of competition events.

Elliott has gone as fast as 178 mph on just motor, and nearly 188 mph in the standing-mile with a single-stage 125-shot of nitrous from a Nitrous Outlet kit, which is controlled by a two-stage Nitrous Outlet WinMax controller.

“Everybody loves the sound of it,” he says. “It’s not the same as a flat-plane crank, but I get tons of compliments every time I track the car. It gets driven all the time on the street, and it’s the Texas Mile record holder for three years for naturally-aspirated S550 Mustangs.”

Thomas Kautz’ “Putty” 1981 Porsche 911 SC (European model) is a street-legal competition platform

Thomas Kautz, of Colorado Springs, Colorado, built his 1981 Porsche 911SC European model, which he calls “Putty,” to be a “full racecar but street legal.” As such, it features a full cage he built himself using 1-1/2-inch diameter, .095-inch-wall 1020 DOM tubing, for a total weight of only 2,400 pounds. He’s wheeled it through many autocross and high-performance driving events in the region.

“It’s only had two short sessions last April in this body configuration,” Kautz says. “Before then, it was mainly stock. I did not build it for a particular class, other than I really want to do the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb.”

So when he tore down the 3.0-liter engine to wring more power out of it, his goal was to increase numbers in the mid-range to top-end — or about 4,000 to 8,500 rpm. So, he selected Web Cam‘s 171e/149i cams, which feature an advertised duration of 294 degrees intake and 284 degrees exhaust with a duration at 0.050-inches of lift of 274 degrees intake and 264 degrees exhaust. Kautz is currently working on getting the ECU tune done, after which he hopes it will make about 350 horsepower and 350 lb-ft of torque on premium fuel with an octane additive. Those are numbers similar to what others with a similar combination have achieved, he says.

“The biggest challenge was doing it all myself at home,” reveals Kautz, “The second-biggest issue was just the sheer cost of everything. Because of that, some parts didn’t get replaced, including the oil pump, intermediate shaft and gears, and some of the valves, which were replaced not long ago.”

The engine received new head studs, Nikasil-lined cylinders, JE 11.5:1-compression ratio pistons, Pauter Rods, and Borla 46 mm individual throttle bodies with 36-lb/hr high-impedance injectors. Porsche Carrera tensioners and serpentine belt drive were used, along with a twin-coil-on-plug ignition, and an Electromotive TEC3 GT engine management system.

“The car and engine have over 300,000 miles on them. I was concerned about reusing any of the engine internals. A machinist friend checked out the crank, and we went over the other items. This is a testament to good clean oil and changing it when you should.”

Although a few gently used items were carefully examined before they were reused, the bulk of Thomas Kautz' 911 build was new, including Nikasil-coated cylinders, Pawter rods, and JE pistons.

Tom Stahl’s “Phat Bee” 2012 Transformer Edition Camaro SS tests the limits of a stock LS3

Tom Stahl’s 2012 Transformer Edition Camaro SS (in 2SS trim) has an LS3 with a six-speed manual. He calls it “Phat Bee.” A Street Legal Performance (SLP) TVS 2300 supercharger makes 7 psi of boost on a stock long-block.

“Sadly, it’s no longer numbers-matching, as the stock LS3 let go at 10 psi of boost,” Stahl says. “Live and learn. When it let go, I had no way to tell what went first. I was over-spinning the first TVS 2300 to make the boost, but the supercharger was scrap either from its own failure or the debris thrown back up from the valves, pistons, rods, etc. It let go at 6,500 rpm in Third, and put two holes in the block.”

Stahl, of Kouts, Indiana, said he installed another long-block, planning to leave it stock. He considered installing an LSA block and now wishes he had, but its cost wasn’t in the budget at the time. “Leaving it stock didn’t last the summer,” he laughs. “It was too disappointing [naturally aspirated], so I ordered another SLP TVS2300.”

The engine internals are still stock, but this time, Stahl kept the stock pulley on the SLP TVS2300, which keeps it to a milder 7 psi. “I’m staying there for now. In the future, a cam, springs, and rockers are a possibility, but I’d need more fueling to make any more power than it is.”

The current fuel system includes Injector Dynamics ID1050X injectors, a DSX Tuning Flex Fuel Kit, an ADM fuel pump control module and ZL1 fuel pump, and a JMS Chip & Performance PowerMAX V2 fuel pump booster.

“I can just maintain fuel pressure with the current fueling mods,” he says. “Dave Steck [DSX Tuning] has an auxiliary system available now in parallel with the stock pump. It would have been much simpler than all the mods I made.”

Tom Stahl’s “Phat Bee” is a 2012 Transformer Edition Camaro SS (in 2SS trim) with a Street Legal Performance TVS 2300 supercharger making 7 psi of boost.

Stahl tuned it using HP Tuners. “PE lambda is .75 on corn. I learned to tune in lambda so it makes more sense to me and is the same regardless of fuel,” he says. “Lambda is monitored by two Bosch wideband oxygen sensors into a pod mount and HP Tuners. Contrary to stock LS motors, this blown setup is leaner on the even bank, which is probably part of the reason I lost the first engine. I only had one wideband in bank 1 at the time.”

Phat Bee runs Kooks stepped headers (1-3/4 to 1-7/8-inches) and a Stainless Works X-pipe dual 2.5-inch exhaust. Currently running stock wheels and tires, Stahl says he needs drag radials to exploit its power. “It’s traction-limited in First and Second with the 3.45 gears, but 60 to 100 mph in Third is four seconds flat.”

Dan Dreisbach Leverages IndyCar Team Skills To Produce This Lightning-Blown LT1

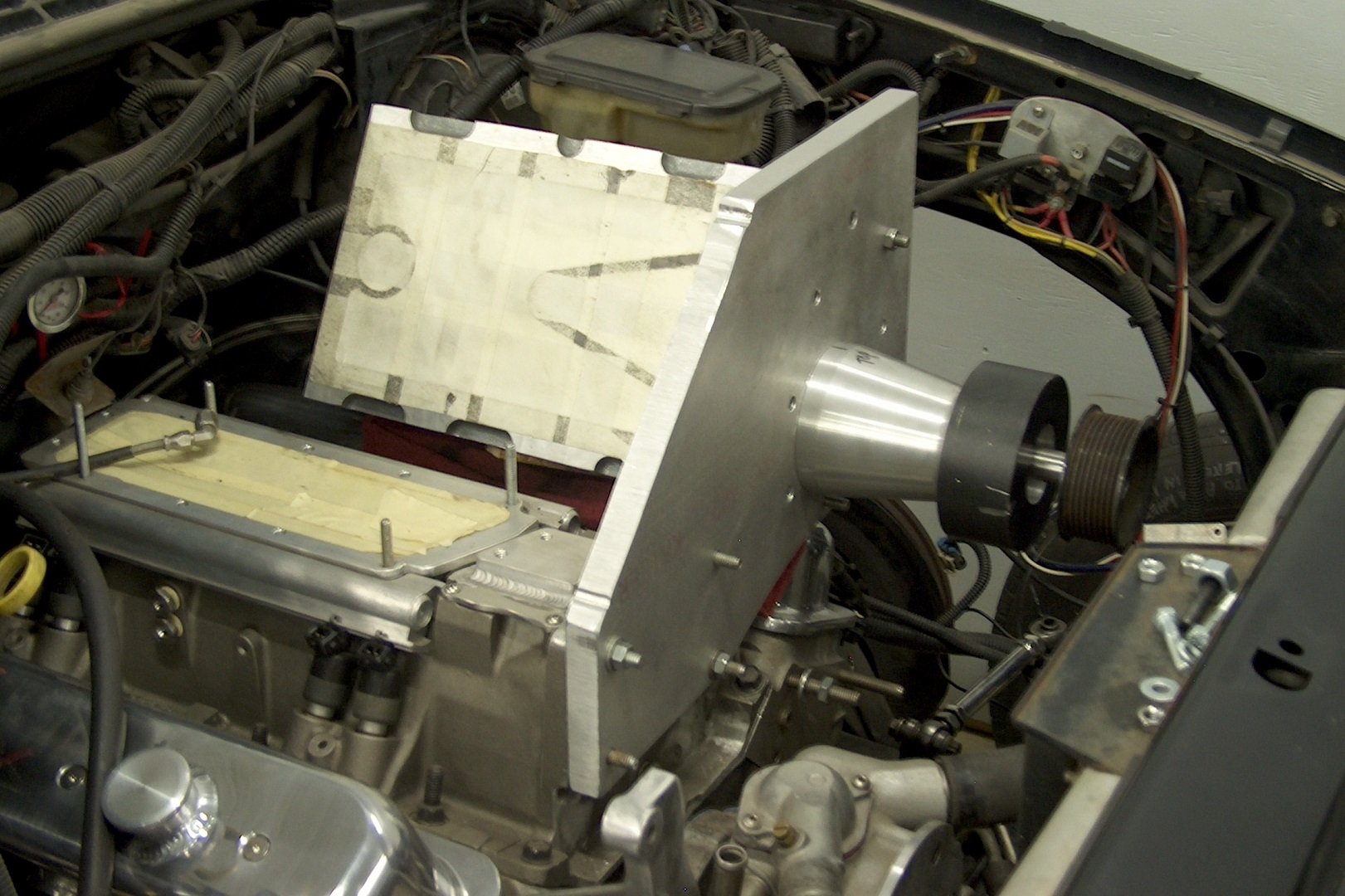

Dan Dreisbach responded to our Facebook post with one of the most unusual and visually interesting combinations, a 1996 LT1 pressurized with a supercharger and intercooler of his own design, aided by 40 years’ experience in complicated projects. He’s paired it with a T-56 transmission in his 1995 GMC Sonoma. He put the LT1 in his truck in 2003 when LS engines were not as common and were unaffordable, he said.

“While I find the LS engines are superior performers, they’re ugly, unless one covers them with fake stuff. And I hate fake stuff.” The LT1, while a traditional small-block, has the advantage of no rear-mounted distributor, which allowed him to place the engine as far back as possible with the stock firewall. He moved the front wheels one inch forward by modifying the lower A-arms and building new upper arms for both aesthetics and weight distribution.

“In the end, with a V8 and blower, intercooler, water, and dual exhaust — every mod I made — the truck only gained 240 pounds overall, with only 30 pounds added over the front. I also don’t care for building things that have already been done a bazillion times. I like to be unique.”

I don’t care for building things that have already been done a bazillion times. I like to be unique. —Dan Dreisbach

Dan Dreisbach honed his skills in design, engineering, and fabrication working on an IndyCar racing team. He drew on those skills to mate a Ford Lightning supercharger with his 1996 LT1.

Dreisbach designed, engineered, and fabricated everything himself. He runs Naked Sculpture, a welding and fabrication shop at his home in Pleasantville, Ohio. He says he spent 19 years working for IndyCar racing teams, starting in 1989 with the Truesports team before working on Bobby Rahal’s team, where he picked up a wide variety of fabrication, welding, and machining skills.

“I seem to be called on most to do work that other machine, fabrication, or welding shops have no interest in doing,” he says. “On the race teams, I was lucky to learn how to do many types of things, so I get to apply those in the work I do for myself and customers.” The LT1 has a stock 80,000-mile short-block, heads, and camshaft, although he assembled it with a head stud kit and copper head gaskets.

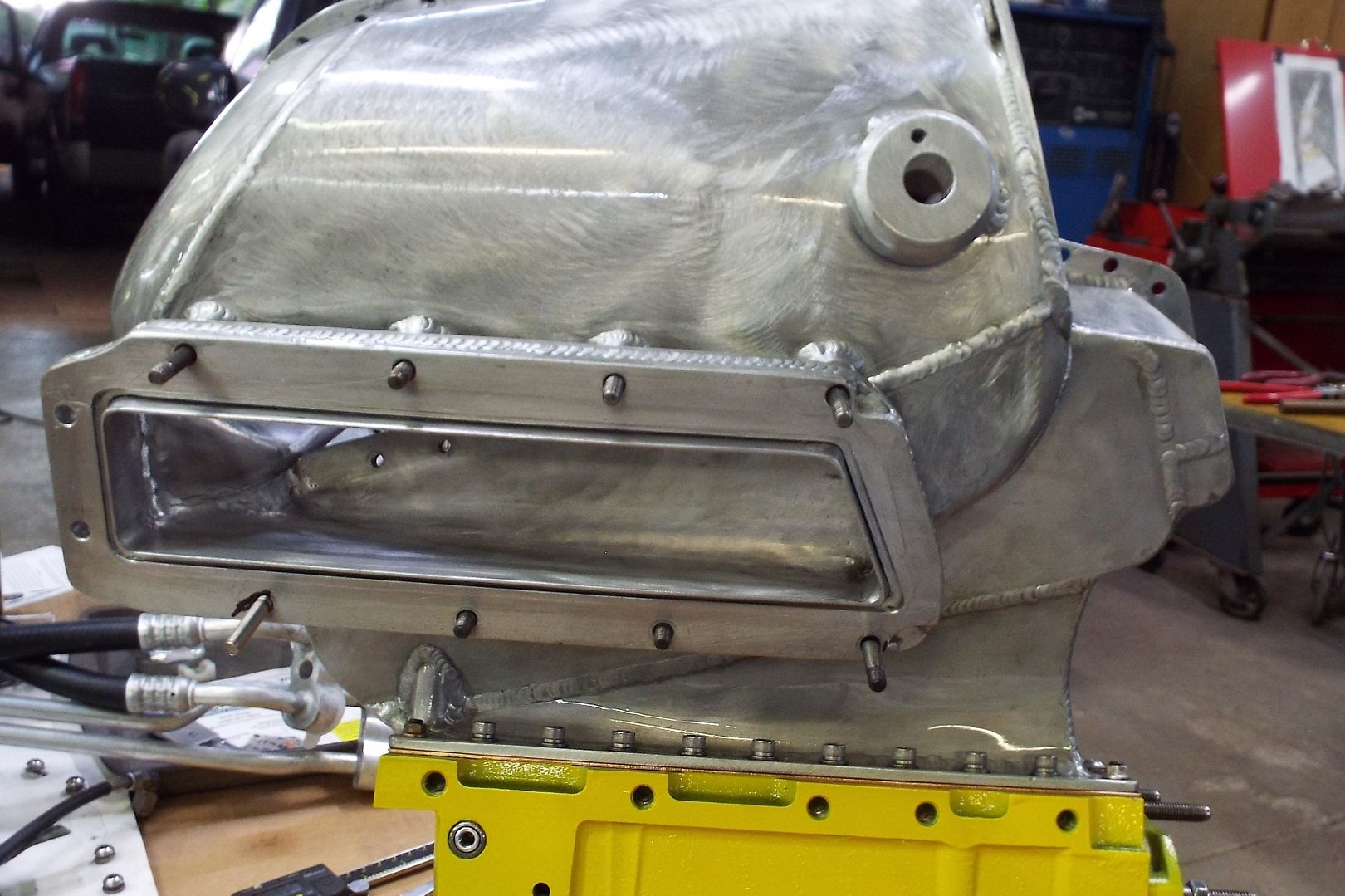

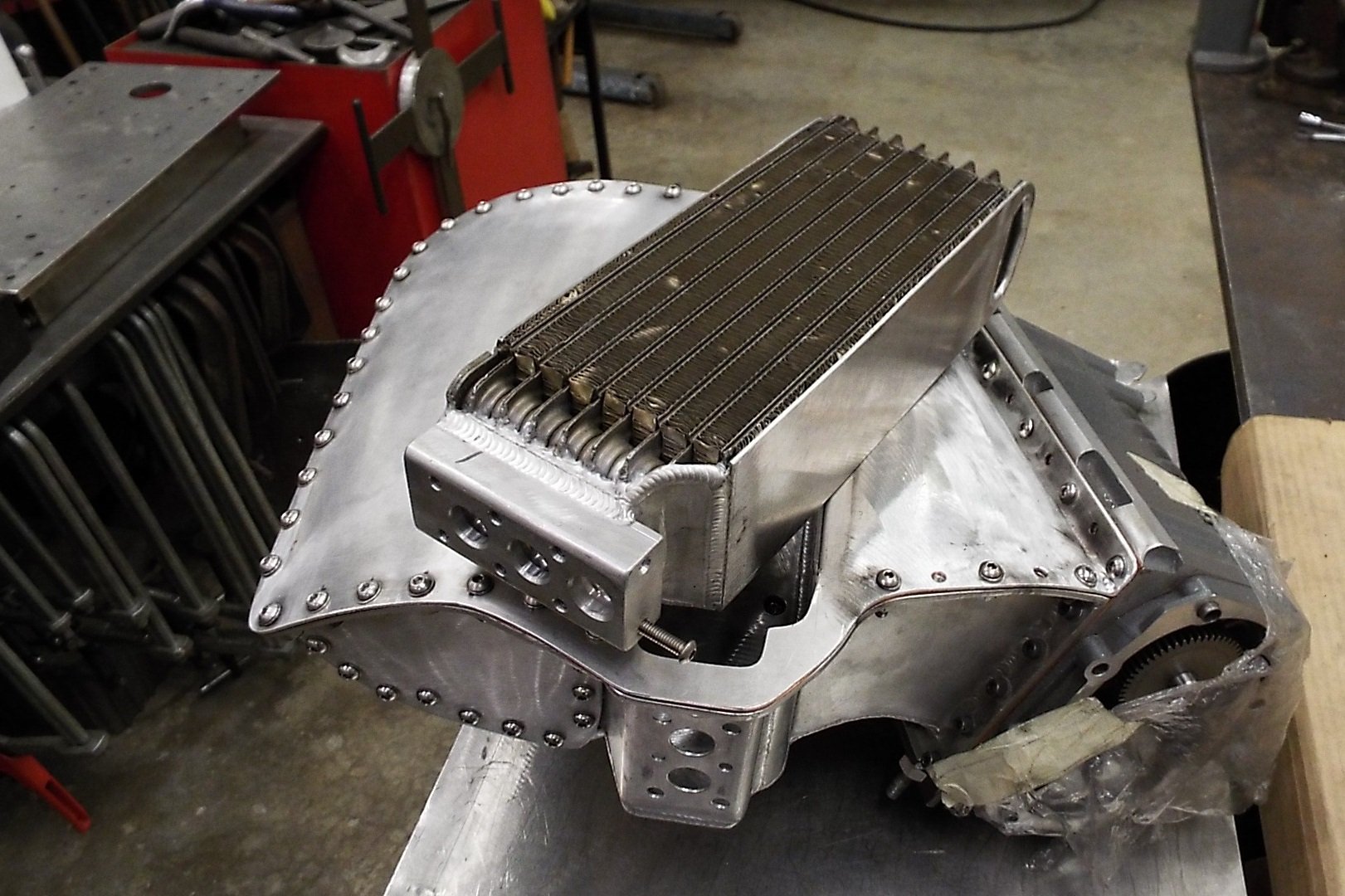

Top-end modifications are limited to Harland Sharp 1.6:1-ratio roller rockers. He sourced a Ford Lightning supercharger (he thinks it was from a 2000 model) on eBay. He made up his own drive system and designed the blower to sit on the left side of the engine, modifying the LT1’s plenum so the boosted air is exhaled into the top of a modified LT1 plenum. He made the water-to-air intercooler in the plenum using a 1969 Pontiac Grand Prix evaporator core. He added an O-ring block to it for the water line connections and modified it so it would fit tightly in the custom plenum.

Dan Dreisbach modified a 1969 Pontiac Grand Prix A/C evaporator core to serve duty as an air-to-water intercooler. He tucked it into his hand-built housing, and whipped up everything in his shop needed to make a Ford Lightning supercharger force-feed his 1996 LT1.

Dreisbach makes his work sound a little easy, but he says he designed the blower plate to mount the blower squarely with the engine. Then he figured out the length of the snout needed by measuring the length of the original drive, minus the mounting plate.

“The new snout was made on the lathe and the mill, and uses the same internal components, bearings, and seals as the original,” he says. “The drive pulley’s diameters were decided by what others had done to get 9.5 pounds of boost. A machinist friend made an adapter to mount the 8-inch lower pulley (bought aftermarket for a Lightning) to a Fluidampr harmonic balancer.”

“I bought the proper carbide insert tool so I could make the upper 3-inch, eight-groove pulley myself on the lathe. The idler mechanism and idler pulley assembly were also custom made, are adjustable, and have dual bearings.” Because the Lightning’s Eaton M112 supercharger normally sits horizontally, the oiling system needed some careful thought, too.

“The oil/gear cavity [normally] holds the amount of oil it needs for long-life with the oil level,” he continues. “When not running, it rests below the seals so it doesn’t ever leak. But with the blower essentially on its side in my application and at an angle, the oil level is too low to properly reach the bearings if it is kept beneath the seal when static.”

To solve the problem, Dreisbach tapped into the pressurized engine oil from the port behind the intake and plumbed it into the blower mount plate, where it enters cavities in the snout.”That directs the oil to the bearings first, then fills the gear cavity. When the level of the oil in the cavity gets to just below the seal, it is allowed to exit a larger port that is plumbed so it can drain into and through the valve cover and down into the lifter valley.”

Turning to his IndyCar experience, Dreisbach made a heat exchanger core from a high-fin-density Marston core that was originally part of a 1996 Lola ChampCar engine radiator. “It was made to be a double-pass cooler, and it has aerodynamic tanks for better airflow. Also, there is a reservoir that holds a stock Lightning intercooler pump that is low in front of the left front tire with a titanium stone shield.”

The combination makes 435 horsepower as an educated guess, Dreisbach says, and includes long-tube stepped headers with merge collectors, a 58 mm throttle body, 9.5 pounds of boost, and Accel 45 lb/hr injectors.

“I did have it chassis dyno’d, but I had two problems at the time that didn’t allow accurate testing,” he says. “I had a bad pair of injectors, and the mass air sensor was too small and was shutting the system down at 4,400 rpm under load. As it was, I got 394 lb-ft of torque but just 311 hp. The changes I’ll have coming soon will be a larger mass airflow sensor and round 100mm throttle body, as well as an oil cooler and remote filter combination that will all be custom made.”

Pat Daly’s Pressurized Big-Block Chevy

Pat Daly, of Streator, Illinois, built his ProCharged 489-cubic-inch big-block Chevy for his Nova 23 years ago, before the family took a front seat to his hobby. Now that there’s more money and life has slowed down a bit, he hopes to improve on the combination. “To be honest, the blower is nowhere nearly big enough for the engine,” he says.

Tired of running into belt-slippage issues from the original serpentine drive system, he finally made his own cog drive. “That worked to get to 18 pounds of boost and a 5.83 at 121mph in the 1/8th. The only problem was I was driving it too hard, and it sucked the teeth through the belt. So on my last 1/8th, I actually was slowing down, and it ended up a 10.57 at 119.” He realized he needed a bigger supercharger, but with his second child on the way, the Nova was put on the back burner.

Pat Daly’s Procharged 489 big-block Chevy Nova has run as quickly as in the 5-second range in the eighth-mile, but belt-slippage issues have him considering installing a larger supercharger or converting to a turbo.

Starting with a “512” casting block, Daly had it converted to four-bolt main caps. A balanced Lunati Pro Mod reciprocating assembly includes 8.75:1-compression ratio pistons (which spec out to closer to 9:1 with his heads). The camshaft is a .680-inch lift intake, .695-inch exhaust, 112-degree LSA solid-roller. The top-end includes rectangular-port, open-chamber heads with .100-inch-longer valves and titanium retainers.

“I used longer valves to try to help with valvespring life since this is essentially a street car. That, in turn, required custom pushrods to get the sweep right, which necessitated using 351CJ rocker studs to get the rockers up, which in turn required the funny bumps on the valve covers you see in the photos. I always told people it was an experimental nitrogen spring setup,” laughs Daly.

Daly converted an Edelbrock Victor Jr. intake manifold to EFI, adding 9/16-inch-bore fuel rails, feeding 83-lb/hr injectors — the biggest ones sold in 1997, Daly adds–and a Precision adapter with a 90mm Accufab throttle body, also the largest available in 1997.

“The ProCharger is either a prototype D1, or the first one they ever sold. ProCharger was not near the company they are today, and every time I have ever had to call them, they tell me I have a P600, and I have to send them a picture of the serial tag and of the blower, and then admit, ‘Yes, it is a D1.’ I know I waited almost six months for it to be delivered after I ordered it. I ordered it before they officially went on sale.”

The fuel system consists of a Weldon 2025 pump and Weldon 2040 regulator, with a -10 supply line and 6-AN return. The injectors are opened by a first-generation FAST sequential controller. Spent exhaust gases make their way out through Hooker Super Comp 2-1/4-inch headers, which flow into four-inch, three-chamber Flowmaster Street Shootout mufflers with turn-downs.

Although his combination has gotten his dual-purpose Nova as quick as into the 5s in the eighth-mile, Pat Daly had to overspin the blower to get those numbers. He is mulling over adding either a larger supercharger or switching to a turbo to get it back on the street and strip.

Daly is mulling over his next steps to get the car back on the street and strip.

“The good thing is I still have it and I am getting close to being able to afford to spend on it again. So now what do I do? Install a ProCharger F2, which is more than plenty, or do I put a turbocharger on it? I need to pull the valve covers and test the springs, and what about that state-of-the-art EFI? Will my old laptop even boot up? Decisions, decisions,” he laughs.

Whatever your taste is in engines, there’s always ingenuity to be found in the American hot-rodder, and isn’t variety what makes life interesting?